Leadership lessons are always fun to explore, although like the analyses of over zealous teachers of English, they should be treated with whole barrel-loads of salt. I have just finished listening to the audiobook version of T. E. Lawrence’s “Seven pillars of wisdom”. Being very interested in leadership development I can’t resist some very brief reflections on the more obvious lessons that I took from his amazing story.

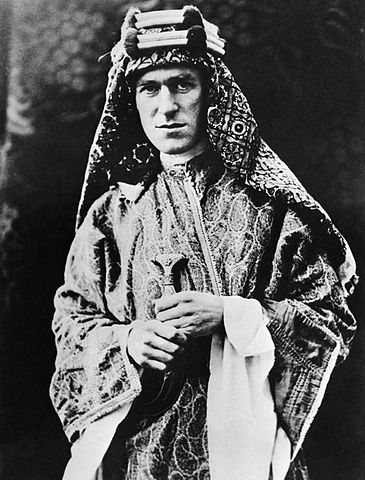

The whole story of Lawrence’s Arabian adventure is easy to find all over the net in various factual and analytical forms. If something a little more dramatic is to your taste then the classic Peter O’Toole movie tells the story in reasonable outline. Briefly, Lawrence was an archeologist who was working in Cairo (as a relatively newly commissioned officer) just before the first war for British Military Intelligence. His principal interest was in mapping the areas of the Middle East to support military operations. Lawrence had developed fluency in Arabic and a keen interest in the culture and politics. It became imperative that the Turkish occupation of what we would now think of as Syria, the Emirate states, Jordan, Iraq and Kuwait was reversed and the Allies able to Consolidate the Middle East. (The map of the middle east in the Ottoman Empire period up to the end of WW1 is unrecognisable to a casual reader like myself). Lawrence conceived a plan to assist the difficult Allied (but principally British operations) by harnessing the movement known as the Arab Revolt. This Arab Revolt was a combination of resentment of Turkish occupation as well as a growing sense of a wider Arab Nationalism combining the many Arabian states of the time. Lawrence persuaded the military authorities to allow him a free hand to liaise with the movement under Faisal. Lawrence then spent two years co-leading a largely guerilla war across huge tracts of the Middle East, finally leading to the liberation of Damascus as the final blow against the Ottoman Turks in Arabia. The main thrust of Lawrence’s insight was that a small number of light-travelling Arabs could constantly damage the Turkish railway network, not to destroy it utterly, but to stretch the Turks in having to constantly repair it across huge distances as well as to suffer the constant problems of poorly provisioned, hungry garrisons as the railway network tried to supply them. Lawrence commented that he personally destroyed 79 railway bridges throughout his two years living and travelling with Faisal’s growing army of the uprising. This campaign against the railways was interspersed by a number of military objectives and even some larger battles in support of the British army’s wider campaign to defeat the Turks and Germany. Lawrence was the intermediary between the British Army and the uprising, although he was mostly living and travelling natively with the Arabs. One of the facets of the story which stokes the romance of this truly epic and unlikely tale was the degree to which Lawrence “went native”; he adopted the Arabian dress, spoke their language, even understanding many dialects, travelling largely by camel, and eating rough with his desert companions. Lawrence’s contribution was rightly considered pivotal, and the help to the Allied and British campaigns vastly outweighed the small numbers of troops, vessels or aircraft committed directly to aiding Lawrence’s requests.

So what were the interesting lessons for me?

- Clear and compelling vision

Lawrence stuck to a very clear line about his vision for Arab independence and an Arab State as a compelling idea. He seemed to believe that this would be in the best interests of the British as well as the Arabs. He appeared to hold a win-win view of the situation and over two years he was convincing to everyone in the Arab revolt; mainly because he was genuine. This was a simple message, which worked extremely well and he gained respect from most and devotion from many. his campaigns were a huge success and he had relatively little material or manpower support from the British. He had a real problem however as he was leading in two-directions. This simple vision motivated and bound the Arabs, however the Senior Leaders of the British Expeditionary Force wanted assistance for their campaign across a dangerously large mass of desert land; the Arab assistance for the campaign was their motivation. Lawrence had to continue to push the idea of the effectiveness of the Arab guerilla operations to General Allenby and the British, while assuring his Arab uprising that the British were also behind them and would play fair by their aspirations. Lawrence never actually believed the British intentions to be honourable and suffered tremendous guilt about his role in promoting a promise of support that he believed was untrue. I think he revealed himself to be predominantly devoted to the Arab vision when he entered Damascus and became the de-facto commander on the ground. He appointed an Arabian acting government to bring smooth running and some quick self-governance to Damascus before a governorship could be established by the British. This interim government lasted for two years in practice and allowed Lawrence in my view to “square the circle over his own belief that the British and other allies wouldn’t keep their promises to Faisal and the Arabs. Lawrence must have felt that he had given them a fair chance to demonstrate good governance and to be in a strong position to negotiate a better settlement. In the end the British and French carved out a settlement contrary to the promises made to the uprising. Lawrence effectively led for two years with the simple and easily understood benefits of the uprising as his daily compelling vision.

- Lawrence was a learner

You can’t underestimate the importance of learning in Lawrence’s career and campaigns. His background in learning about the politics, geography, history and culture of the Arab Nations was what compelled Lawrence to spot the opportunities offered by fanning the flames of the revolt. His command of the language marks him out as a very committed and effective learner. His use of military history and theory from his own learning led to his own detailed analysis of the military situation. (He invoked the military thinking of Clausewitz many times in his comparative breakdown of the unique opportunities of the situation). He learned the art of Camel riding and care, (no small feat), as well as the technicalities of railway demolition. Lawrence eventually innovated in this area too with his “butterfly charges” designed to twist and damage metal railway sleepers instead of overusing charges to completely destroy thus removing the tidying and clearing phase when the Turks came to repair and rebuild. There was little doubt that Lawrence was a clever leader, but he showed a willingness to work at further learning throughout.

- Courage

Lawrence was very, consistently and sometimes biblically brave. He was personally injured many times during his military excursions and yet doesn’t ever seem to have allowed this to cause him to to avoid danger where he felt the gains were worth the price. He was not often foolhardy however, he simply acted in the best interest of his cause as long as his analysis of the situation told him it was the right course of action. He was singularly courageous in travelling alone with Faisal’s Arabs when he became detached from his fellow British officer class. For two years, with only brief breaks he threw his lot in with a people who he often considered frustrating and hotheaded, to the exclusion of more familiar company and conversation. In appearing back with the British Expeditionary Force and retaining his adopted Arab dress, he showed tremendous self-confidence and courage, knowing he could be ridiculed or ostracised. In playing one side against the other to get the outcome that Lawrence himself though best for all, real bravery was necessary as there is a fine line between exercising the trust that General Allenby and others had invested in him, and abusing that trust to the detriment of his own national interest. Lawrence was taking a gamble to achieve something, and though it was influenced by his own skills and leadership more than by any imaginary dice, he must have had a million safer options; these options were not suited to a true leader however.

- Team building

Lawrence seemed to understand that the use of the skills and connections of a large network of people was essential to his task. Although he was often portrayed as a heroic figure, alone, gazing into the distance on camelback, the reality was that he was a prodigious networker. Lawrence was able to engage socially with a wide variety of people for his campaigns, and more often than not, emerge with either an ally or an advantageous deal for the campaign. He networked extensively among the Arab tribes and their leaders gaining wide respect and many Arab guerilla troops on an often ad-hoc basis as he met the various friends or relatives of his main uprising leadership group. He networked with the various British and occasional French commanders he partnered. The naval support ships captains were happy to dine with Lawrence and planning for the most effective support the ship or crew could give would often be laid. In short, Lawrence certainly did not merely go native with his Arab “army” to be seldom seen again, instead he networked like crazy identifying resources and people to support his objectives more or less constantly. This is in addition to his dealings with almost everyone around him. By and large he seems to have strongly understood the principle that you follow others when they are better at something than you are. One illustration of this tendency was illustrated when a private, driving the Rolls-Royce armoured car that had just conducted a successful demolition raid against the Turks, suffered a suspension collapse within 10 minutes of the pursuing Turks. Lawrence observing that the armoured car was of immense value to the Turks, and that they may have to abandon it to escape on foot, wrote great praise for the private. This driver taking in the situation, realised he was in effective command according to Lawrence, and he quickly coordinated the raiding party to improvise a suspension support for the 5-ton vehicle. Lawrence was happy to follow when he knew it was wise. He did likewise in the desert, when he learned from experienced Arab raiders and deferred to their advice as it was often his most profitable course. He in fact realised that following Faisal himself was a more effective way of jointly leading than to propose anything as crass to the Arabs as co-leadership since, in rallying and working the tribes and families, Faisal was simply outstanding; Lawrence followed when others were better placed to lead.

- Angst and edginess

I have used this odd phrase because I really don’t know how to say “nuts, but in more of a good way than a bad way” without it sounding really insulting. Back then to his “edginess”; in many leaders there is a distinctly fine line that seems to be walked between stability and madness. Lawrence had a distinctly determined and obstinate nature. Some biographers have commented that his mother beat him a lot in his childhood due to his obstinacy and determined nature, perhaps his slightly off-the-leash approach to being in the British Army was simply an extension of some deep need for independence in his nature. In his autobiography, he often expresses his desire to surrender to the will of his seniors, seeming almost to blame them for giving him too much freedom! It is interesting that his biographers regard it as an established fact that he later paid a military colleague to give him beatings. There are many other examples of the slightly eccentric facets to Lawrence’s nature, but suffice to say that he was a little tortured as well as unusually driven. This is interesting in that we can encourage those who want to learn leadership to model aspects like, teaming skills, courage, vision, learning disposition etc. You really can’t ask someone to become a bit more tortured and driven; I believe that many leaders are driven because they have some mild mental instability.

“T.E.Lawrence, the mystery man of Arabia” by Lowell Thomas (photographer) – Lowell Thomas. “With Lawrence in Arabia”, book is in public-domain, full text available at Archive.org; originally from University of Toronto. .. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:T.E.Lawrence,_the_mystery_man_of_Arabia.jpg#/media/File:T.E.Lawrence,_the_mystery_man_of_Arabia.jpg