Written by Jay Helbert

“A man must shape himself to a new mark directly the old one goes to ground.”

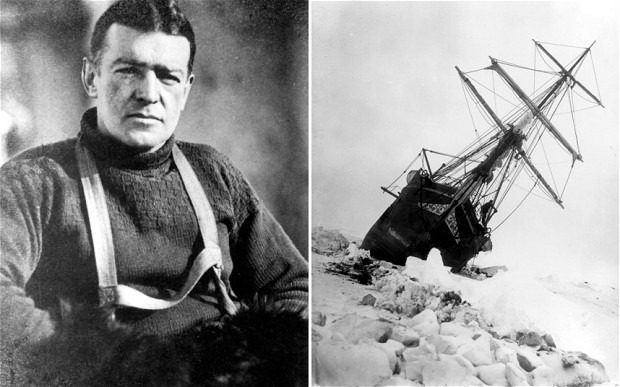

On the 27th October 1915 the Antarctic exploration vessel the Endurance finally started to break up after being locked in pack ice for ten months. The 28 man crew saw not only the destruction of their home, but the loss of their lifeline. Their mission to be the first crew to cross the Antarctic landmass via the South Pole would not come to pass and their chances of ever reaching home must have seemed remote indeed.

Yet nobody panicked or gave up hope; there was no mutiny and the crew set about the business of salvaging what they could from the ship and setting up camp on a nearby ice flow. It is hard to believe that the whole crew met this disaster without despairing. In fact this was not their last blow. The crew spent a total of six months living on an ice flow, during which time they suffered from exposure, frostbite, and hunger so bad that they had to shoot and eat their dog teams. When they finally managed to get off the ice and launch their three small boats, they sailed for two weeks in tumultuous seas in temperatures well below zero. Blisters, seasickness extreme discomfort frostbite and exposure all took their toll as the three boats searched for land, anchoring in the lee of icebergs by night.

Every member of the team survived and throughout the entire 24 month ordeal discipline, performance and team spirit remained high, due in the main to the leadership displayed by Ernest Shackleton, Frank Wild, Frank Worsely, Tom Crean and other crew members.

Though life in the classroom and the staff-room can sometimes be tough, there are relatively few school scenarios that represent as big a challenge as those faced by the crew of the Endurance, yet there are leadership lessons that cross from 1915 to 2015 and from the Weddell Sea to twenty first century schools.

1. Define the task at hand in with honesty

“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success.”

The above text has been attributed to newspaper advertisements placed by Shackleton whilst recruiting for his expedition. In fact it is disputed that the advertisement was ever placed and is possible that these words were fabricated by biographers after the event. Shackleton himself never makes mention of such an advertisement in his account of the mission, ‘South – The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition 1914 – 1917”, however like much apocrypha there is a spirit of truth within. The crew were fully aware of the dangers and risks they faced on the mission and the personal logs of a number of crew members kept during the trip show a clarity of purpose and a realistic acceptance the trials to be faced. Thus when times got difficult, nobody was taken by surprise or felt they had been deceived; they were prepared for the blows they faced.

2. Don’t turn crises into dramas – remain emotionally anchored

When it became clear that the Endurance would not make it out of the pack ice, Shackleton knew that to play down the problem would be to risk losing the confidence of his men, yet to show any sense of doom would only encourage despondency.

“It was at this moment Shackleton showed one of his great sparks of real greatness. He did not show the slightest sign of disappointment. He told us simply and calmly that we would spend the winter in the ice.”

- Alexander Macklin, Ship’s Doctor,The Endurance

Through the ice bound months, Shackleton insisted on the continuance, as far as possible, on routines. Dog teams were trained, scientific surveys undertaken, samples collected and equipment maintained. Stores were moved from the deteriorating ship into safer quarters and hunting parties gathered seal and penguin meat and blubber. These routines not only ensured provisions were maintained, but also gave every member of the team a sense of normality; it is hard to imagine you are in a life threatening situation when the boss is asking you to collect soil samples from the ocean floor. Later in the mission, when Shackleton left 22 men on Elephant Island in the charge of Frank Wild whilst he and a skeleton crew sailed off in search of help, Wild formed the habit of rolling up his sleeping bag every morning and telling the men he was getting ready as ‘the boss might return today’. This understated optimism and use of routine stopped despondency setting in amongst the men awaiting rescue.

3. Plan for all contingencies

As when Nelson fell at Trafalgar, and his captains continued on to victory having already anticipated and planned for this eventuality, so Shackleton and his crew knew what to do in the event of the Endurance becoming trapped in heavy pack, and even crushed.

At any given part of the mission, Shackleton had several plans in place to suit varied but predictable changes to their situation. Such detailed planning both before and during the expedition meant that the crew were able to abandon the ship to set camp on the ice flow as if it was all part of the anticipated plan. When the pressure of competing ice flows caused the necessity of moving camp, and the Endurance finally sank, Shackleton merely told his mean “Ship and stores are gone – so now we’ll go home.” His private diary entry at the time shows more of his real frame of mind, “A man must shape himself to a new mark directly the old one goes to ground. I pray God I can get the whole party to civilisation.” The next part of the plan was to take to the Ship’s life boats and row or sail in search of land, however, this plan had to be constantly checked and repeatedly postponed until the ice was loose enough not to pose a threat. If Shackleton had stubbornly stuck with the Endurance, or forged ahead on the boats too soon, he and his crew would have perished. It is this ability to plan for many contingencies, and then judiciously apply the plan best suited to prevailing conditions that mark the genius of his leadership.

4. Keep the team together

The faith that the men put in Shackleton bordered on devotion. This was in no small part to his determination that all should come through. When the ice began to melt sufficiently to launch the three lifeboats the crew had rescued from the Endurance, the officer of each boat was commanded to stay within hailing distance of the other two at all times. Two of the boats, The Dudley Docker and the James Caird had larger sails and were more seaworthy than the third, the Stancomb Wills and could have easily made landfall faster. However, when the smaller mast in the Stancomb Wills snapped, Shackleton ordered his own boat to tow the smaller vessel. Such togetherness gave every member of the crew the knowledge that ‘The Boss’ would never let any of them down. This sense of confidence was vital for the 22 men who subsequently waited for four months on Elephant Island for Shackleton and Worsely. Many of the men attributed their ability to endure on the faith they had that Shackleton would return for them.

There were times, of course, when despondency set in, or men began to question Shackleton’s decisions. Some wanted the crew to take to the lifeboats much sooner than was safe and at other times some men questioned the shortening of rations. At these times, Shackleton did not chose to ostracise or discipline these men, rather he gave them important jobs to do and billeted them in his own tent. Thus they saw that their role was being valued and they got a better sense of the reasons behind Shackleton’s decisions.

There are also very diverting tales of the crew organising the ‘Antarctic Derby’ where dog teams raced each other whilst the rest of the crew took bets, and games of football on the ice. Such diversions were calculated to keep the team’s spirits up, but also to pull them together and bond them.

5. Celebrate success but don’t get carried away

There are many moments in Shackleton’s account of his expedition that stand out but perhaps the starkest happens when he, Worsley and Crean, who sailed to South Georgia with a skeleton crew in search of assistance, were on the brink of salvation. These men had spent over 18 months stranded in pack ice, traversed shifting ice flows, left their comrades on Elephant Island to undertake a three week voyage in the open ocean in a lifeboat and then hiked for ten days over uncharted wilderness filled with mountains and glaciers with less than basic equipment. Through all of this they had survived on pitiful rations and very little respite. There is a tremendously moving passage in ‘South’ that describes the moment the men saw before them a whaling station and their first sight of other humans in two years. This was the moment when they realised they would make it and the three men, by way of celebration and without a word, turned to one another and shook hands.

All very British and stiff-upper-lipped you might think, but this account is typical of the way the crew marked successes. There were moments of self-congratulation to be sure, such as when landfall was made on Elephant Island, and then on South Georgia, but the men never rested on their laurels and one eye was always on the next part of the mission – thus focus on the ultimate goal was retained.

6. Never give up on what really matters

After reaching the whaling station at Stromness, South Georgia on May 20th 1916, Shackleton immediately began recruiting a ship and crew to rescue his comrades. There were still 22 men on Elephant Island, many of whom were invalided and were completely reliant on ‘the boss’ to rescue them. Shackleton used the resources of several nations to attempt four crossings to Elephant Island over three months, but as another Antarctic Winter took hold, he was forced to turn back the first three times and risked having another ship bound in pack ice. It was only on the fourth attempt in a steel steamship unsuitable for sailing in the heavy ice of an Antarctic winter that the pack ice opened just long enough for a rescue to be achieved. Throughout these three months, it was only Shackleton’s drive, zeal and perseverance to his goal of securing the survival of all 28 members of the expedition that ensured this final attempt even took place at all. The small Chilean vessel, The Yelcho was ill equipped for tackling sheet ice and the rescue on the 30th August 1916 was made during some of the harshest weather of the season. Few captains would have attempted the risky voyage that ultimately relied on a unique combination of skill, determination and, as Shackleton out it, providence.

7. Build and make use of effective Leadership Teams

Shackleton knew that he had a capable team of officers around him and that the scientist, cook, carpenter and seamen all had the ability to lead. When taking to the boats, he relied upon the superior navigational abilities of Worsely to guide the party and when undertaking the overland trek across South Georgia, Crean’s resourcefulness meant that he was a natural choice to lead alongside Shackleton. The officer who is most lauded with praise in ‘South’ (though was about the most unsung hero of the party) was Wild. When the crew landed at Elephant Island, they were in a bad way and even Shackleton admits to feeling thoroughly wearied by the sea voyage. He noted, however that Wild, who had held the tiller of one of the other boats, disembarked with his accustomed poise that ‘was never dented by success or trial’. Because of Wild’s ability to inspire confidence in the men, Shackleton knew he was the ideal officer to take charge of the Elephant Island shore party that formed the main body of the crew and consisted of those not fit enough for onward journey. Wild was able to lead these men in the creation of a camp on a narrow spit of beach wedged between the open sea and sheer cliffs. A camp that sustained the men through four months of Antarctic winter and temperatures that got as low at 50⁰ below freezing. Shackleton puts the credit for the survival of these men firmly at Wild’s door.

Shackleton’s leadership was outstanding, but this alone would not have saved the crew of the Endurance. The survival depended upon the skill of the cook to create meals out of the most basic ingredients in the most trying of circumstances, the inspiration of Wild and the navigational expertise of Worsely, the survival instinct of Crean, the surgical skill of the two ship’s doctors and the ability of the men to keep each other sustained and motivated during two Antarctic winters.

By honestly diagnosing and defining the task at hand and planning appropriately as well as remaining emotionally stable at times of success and crisis, we can adapt and implement our plans whilst ensuring success by doggedly sticking to our ultimate goals. Moreover, by employing inspirational team management, interdependence and bringing dissenters on board, we ensure that every member of the team performs at such a level that the team outperforms what the sum of its members would otherwise have been capable of. Above all this is the notion that leadership does not rest solely in the hands of the most senior person, rather it exists as a gestalt of the wider team – Shackleton would never have made it off the ice if he was alone.